The nutritional quality of foods is a very broad topic that enters into a number of concerns, most of which are centered on issues that occur after a food is harvested – i.e., what someone has done to a food, not the quality of the source food itself. Considering the vast number of things we can do to foods, this qualitative definition turns into a gigantic combinatorial problem and becomes a discussion that takes focus away from the nutritional quality of the source food. If the discussion is restricted to only the source food and the very first steps in processing, then the issue of quality is much simpler. In essence, when you have a pure source food, you are in control the amount of processing, you choose the additives and you determine the method of preparation. The issue now is to determine what you consider the best ingredients. Aside from balance and composition (discussed elsewhere), topics of concern are, source, taste, variety & use, and preparation/retained nutritional value.

The source of a food is where and under what circumstances it originated. In this manner, start to differentiate between two of what may appear to be the same thing – e.g., feed-lot beef versus range/grass-fed beef. It is also important to understand “Certified Organic” versus “other”. Notably, not just the food, but the farm itself must be certified organic, which requires avoiding the use of synthetic chemicals (e.g., fertilizer, pesticides, GMO, etc.) – and that the farm itself has been free from of such chemicals for some time – and specific restrictions on livestock feeding, housing and breeding (e.g., fed organic feed, no exposure to growth hormones, etc.). Note that such certification must be backed by documentation and is overseen by certifying agencies operating under well-defined quality standards. Additionally, there are three forms of organic labeling – “100% Organic”, which is as it sounds, “Organic”, in which > 95% of the content is certified organic, and “Made With Organics”, which must contain > 70% organic ingredients. In this sense, 100% Organic is likely the source food (raw or with very little processing) and “Organic” contains trace amounts of ingredients that are not certified organic (e.g., sea salt, non-organic spices, etc.). “Made with Organics”, although a step in the right direction, does not immediately convey the organic standards, in that processed foods may contain up to 30% ingredients that you may not want – think of spaghetti sauce made with organic tomatoes and high-fat, feed-lot, rBST ground beef. In this regard, it is best to read the label in greater detail.

The source of a food is where and under what circumstances it originated. In this manner, start to differentiate between two of what may appear to be the same thing – e.g., feed-lot beef versus range/grass-fed beef. It is also important to understand “Certified Organic” versus “other”. Notably, not just the food, but the farm itself must be certified organic, which requires avoiding the use of synthetic chemicals (e.g., fertilizer, pesticides, GMO, etc.) – and that the farm itself has been free from of such chemicals for some time – and specific restrictions on livestock feeding, housing and breeding (e.g., fed organic feed, no exposure to growth hormones, etc.). Note that such certification must be backed by documentation and is overseen by certifying agencies operating under well-defined quality standards. Additionally, there are three forms of organic labeling – “100% Organic”, which is as it sounds, “Organic”, in which > 95% of the content is certified organic, and “Made With Organics”, which must contain > 70% organic ingredients. In this sense, 100% Organic is likely the source food (raw or with very little processing) and “Organic” contains trace amounts of ingredients that are not certified organic (e.g., sea salt, non-organic spices, etc.). “Made with Organics”, although a step in the right direction, does not immediately convey the organic standards, in that processed foods may contain up to 30% ingredients that you may not want – think of spaghetti sauce made with organic tomatoes and high-fat, feed-lot, rBST ground beef. In this regard, it is best to read the label in greater detail.

The most unconscious gauge of quality is taste, which is often also related to source (Note: This applies to minimally processed foods, where flavor of the source food is not overwhelmed by other ingredients). Take tomatoes, for instance, which may be non-organic or organic, with both these varieties available at a grocery store or a farmer’s market. It is interesting to taste-test these four different sources against each other. Organic tomatoes may taste better than non-organic, with the farmer’s market version tasting the best. The general phenomenon here is that most organic and farmer’s market sources tend to let produce ripen more before picking – in turn, enhancing the flavor. The farmer’s markets, generally sourced closer to the point of retail, let fruits/vegetables ripen the most before harvest, so flavor is more pronounced. There are also nutritional differences related to degree of ripening – e.g., amount of lycopene in a green versus red tomato – however, comprehensive nutrition at this level is largely underfunded/understudied, so the full breadth of benefits regarding the maturity of source foods are presently not fully understood. Regardless, taste in relation to certain nutrients, and overall edibility, are important personal considerations when choosing foods.

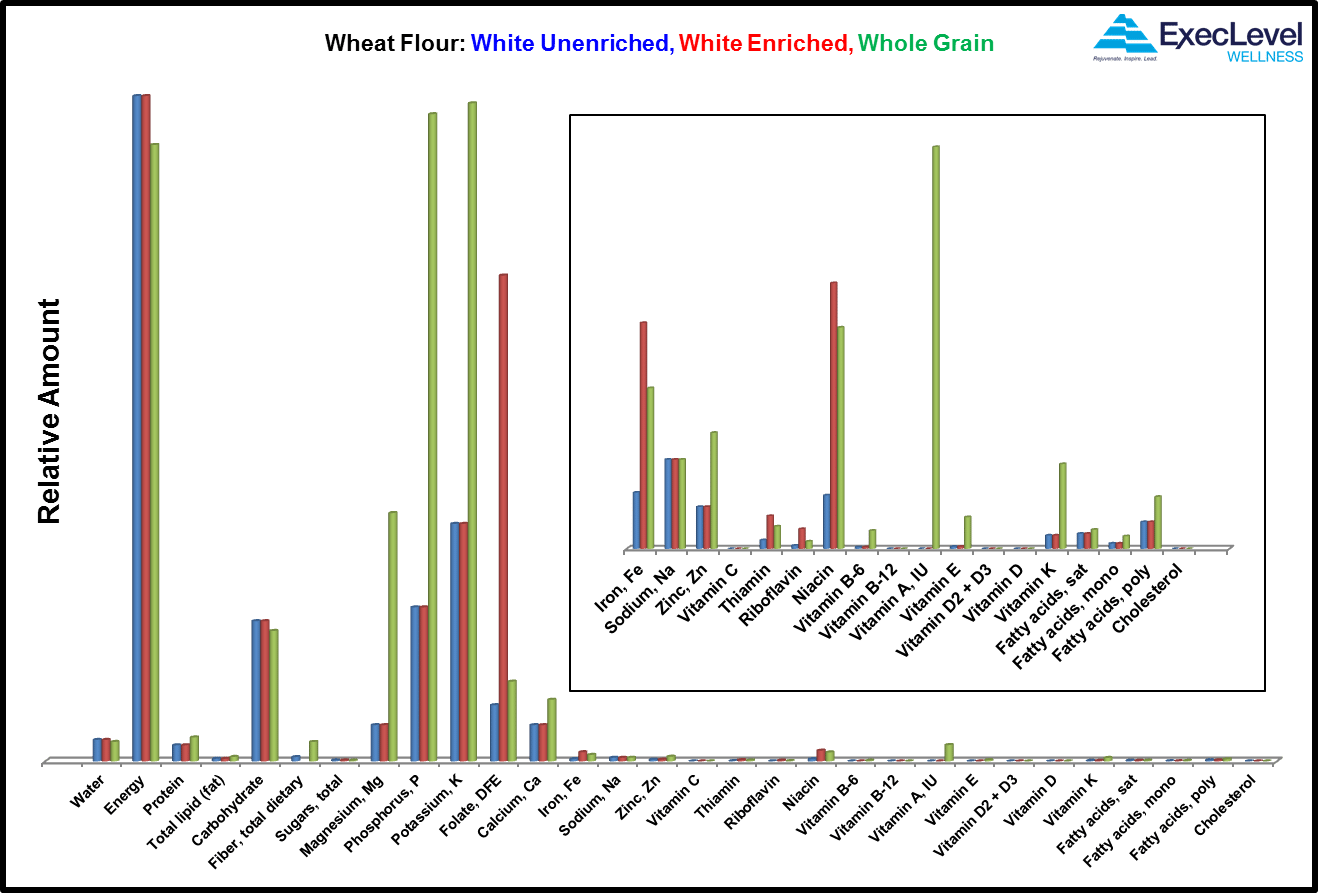

Source food’s variety & use also goes towards nutritional quality. The easiest way to think about this is to make a loaf of bread and compare it to bread from a commercial bakery. Both will contain the same rudimentary ingredient – flour – from sources as described above. The flour, however, can stem from hard or soft varieties of wheat and can range from whole grain – to – bleached/enriched. The different grain varieties significantly alter the nutritional composition of the flour (e.g., the hard varieties contain ~ 30% more protein than soft varieties). The different treatments of any one variety (going from grain – to – flour) also significantly affect the nutritional value of the flour. In the simplest sense, going from whole-grain to enriched-white reduces the amount of protein and fiber, and nutrients that are removed or destroyed during the processing are selectively added back – e.g., Folate, Iron, and Niacin may be added back, whereas Vitamins A and E and elemental minerals Mg, P, K may not. In any event, the nutritional quality of the flour is related to the type of wheat and the very first steps in its processing. Evaluation of the other ingredients will usually turn up similar differences. Of particular interest is the ingredient used as a sweetener – although it is not required, it usually makes bread a little tastier. Here, choices range from refined sugar – to – high fructose corn syrup – to palm sugar (and beyond). Regarding trace minerals, brown sugar is found to have more than refined white sugar, and palm sugar is found to have even more than either of these. The comparison goes on – weighing the nutritional quality of one versus the other – but the take home point is that you can also add in trace minerals when sweeten bread. Taken further, this sort of comparison can be made with almost all source foods – source of carbohydrate (e.g., palm or refined sugar), protein (e.g., red meat or fish), etc. – with, in many cases, the judicious choice of ingredient (and type of first-step processing) significantly affecting nutritional quality.

A last (but far from final) consideration of nutritional quality is that of preparation in relation to retained nutritional value. Most nutritional data (e.g., from the USDA Nutritional Database: http://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/search) are given as values in foods as you would buy them from a supplier. In short, the values are those you start with. As may be imagined, these values will be altered during your preparation; as an extreme example, roasting a salmon fillet to the point of charcoal will significantly alter its nutritional quality relative to raw sushi. Perhaps a better example is a simple potato, which in the raw state contains starch (long-chain carbohydrates) in relatively indigestible forms. Upon cooking these starches become more digestible by being more accessible to enzymes (amylases in your body) that convert starch to simpler sugars. A raw potato, however, is not without benefit, as the resistant starches are a form of dietary fiber and are also found to influence gut microbiota. Thus, depending on how it is prepared, a potato can serve as fuel for you, your dietary fiber (plus nutrients for the bacteria in your digestive tract) or somewhere in between. Such differences in chemistry and how they affect nutritional quality (particularly when eaten) are fairly widespread across foods and should be considered during their preparation.